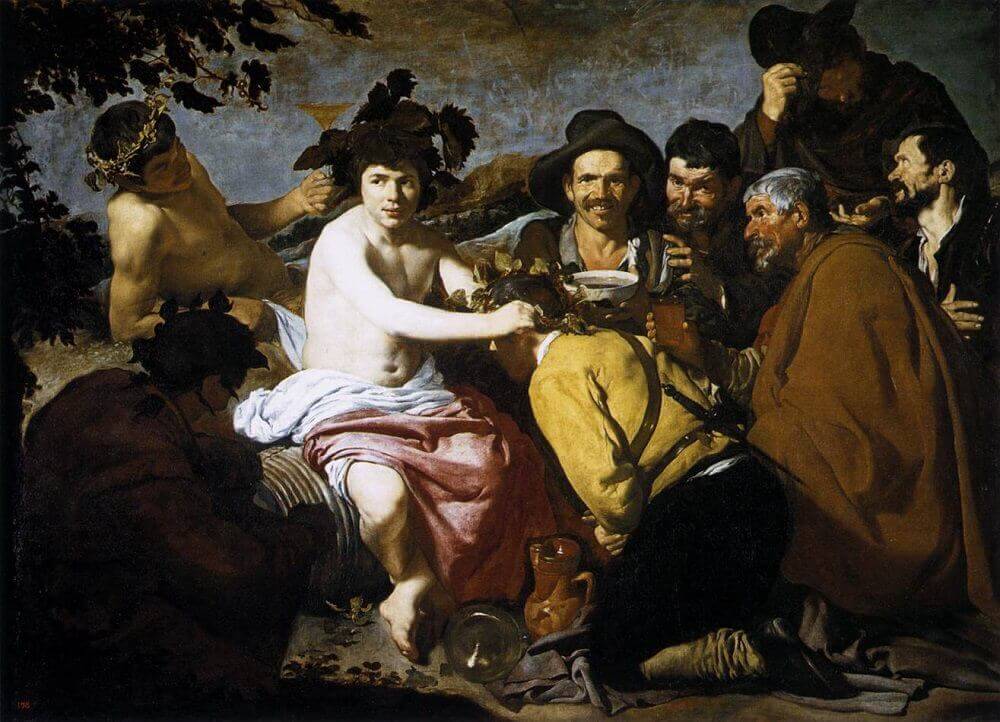

The Triumph of Bacchus, 1629 by Diego Velázquez

This work could be judged typical of the admittedly vulgar realistic tendency of the first paintings of Velázquez; in fact, almost a prank on a grand scale. A Frenchman wrote only a few years ago: "With his brush he sweeps the gods away, and it is no longer Bacchus, but an imp acting the part of Bacchus." The traditional title, The Drunkards, seems, in its turn, to arouse the scorn of the court scholars for this paradoxical Bacchanalia in modern guise, appearing as it did at a moment in which this subject, erotic and Arcadian at the same time, was very fashionable, with the spread of the famous Ferrara masterpieces of Titian, which only a short time afterwards reached Madrid. Velázquez is certainly joking; his painting is, as it were, an anthology of all his juvenile production. We can see the model of Acquarolo; there is an echo of the powerful characterization and violent colour of the "bodegones" of Seville, and of the burning irony against the idealization of mythology, promoted by Renaissance classicism, and also against the conceptual abstractions of the mannerists. But we are at a moment in which the painter, with six years' activity at the court behind him, and famous as a portrait-painter, has irrevocably overcome his juvenile, polemical taste and aggressiveness. The work is, in a certain sense, a posthumous homage to his own youth. Moreover, it is erroneous to consider it iconographically, as is mostly the case, as a photographic example of plebeian realism-festivities in the square or the inn. It was hung in the king's bedroom, and was placed by Velázquez himself beside Tintoretto, Veronese, Rubens, Carracci, Pietro da Cortona. His motif derives from an engraving by J. Saenredam, which inspired the Bacchus of Michelangelo and which Schonaeus commented on in the following verses:

Father, Bacchus, prostrate before you,

We begyou in supplication to grant us your gifts.

Those gifts that dispel grief and sadness,

And free our hearts from painful worries.

Bacchus, as a dispenser of joy, was the object of a real cult in the first half of the seventeenth century: Caravaggio, for example, because of whose Manfredi, possibly, Velázquez re-adjusted himself. The characters staring down at us from the canvas do not attract us in reality; they .invite us, in a friendly way, to free ourselves from tribulation - to dream. The glazed colour, too, and the phosphorescent light have an extremely transfiguring function.