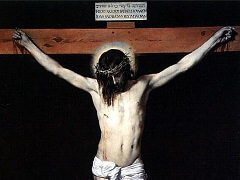

Christ on the Cross, 1632 by Diego Velázquez

Christ, on the Cross, expresses a supreme dignity; this because of his simplicity, his humanity and the admirable absence of both physical beauty and ugliness. This body is not ugly, as in El Greco; much less is it beautiful, as it is in Francisco Goya. It is not athletic, as in Michelangelo's paintings; it is not a spectre, as in certain primitives. It is noble, and it is all. There is no face, because it is hidden by the hair. There is no blood, to quench the thirst for compassion. He has no men around him, their faces showing passions. He is accompanied by neither landscape, nor sky, nor meteorological or prodigious phenomena. He was a just Man, and He is dead. In His supreme dignity, He is alone." Thus, in 1939, before this placid reduction of the divine to the human, one of the greatest critics of the Baroque, E. D'Ors, paid homage.

Christ, on the Cross represents a fundamental moment in Spanish religious art - in which naturalism, condemned by the Church of Rome, enjoyed a very wide development in the name of the triumphal apotheosis, on a popular basis - almost as a polemic against Baroque.

This painting, moreover, constitutes a decisive turning-point, at least in the spiritual field, in the career of Velázquez. In fact he resolves his religious problems, originally characterized by the tendency towards expressionism and sublimation, in connection with El Greco and Caravaggio. Only a decisive lowering of mystical and eschatological values could allow such a balance to be struck between subjectivism and reality, between the image of faith and the image of nature. However, only the progressive diminishing of tension towards the transcendent could allow Velázquez to express his wealth of human and earthly interests.