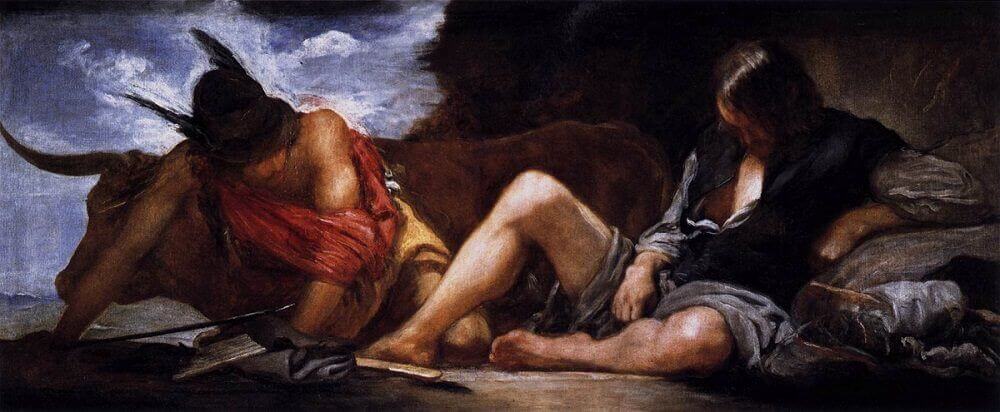

Mercury and Argus, 1659 by Diego Velázquez

According to the myth, Argus was a prince from the Peloponnesian city of Argos who had one hundred eyes. Since fifty of them were open at any given moment, Juno ordered him to stand guard over the young Io, who had been seduced by Jupiter and then changed into a cow. Mercury, sent by Jupiter, lulled Argus to sleep with the sound of his flute, and then he cut off Argus' head (or stoned him to death). Juno scattered the eyes of the slain Argus on the tail of a peacock, after which the bird was devoted to the goddess.

Here again, Velázquez transforms a mythological and supernatural event into a realistic scene with such overpowering truthfulness that it seems more appropriate to a picaresque novel than to a legend from antiquity. The two protagonists of this genre scene transport us directly into the world of the p'icaro of La Vida de Lazarillo de Tormes, or of Cervantes' Don Quixote and Novelas ejemplares. The pauperism in Spain during the so-called Golden Age and the hunger that was a major preoccupation of the people fostered the prevalence of vagabonds who played a prominent role in everyday Spanish life. However, although "pilfering" held a special place of honor, comical pranks and abominable tricks played on blind men also frequently found their way into these picaresque novels. Like the writers and poets who were his contemporaries, Velázquez utilized his genius to become a pictorial chronicler of the times, by virtue of his incomparable brush instead of the pen.

Justi believes that Argus' legs were inspired by the sculpture of the Dying Gaul that Velázquez may have seen in Rome, while de Tolnay sees in Argus' body a similarity in pose and execution to the nude youth at the right above Ezekiel on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

The extreme technical fluidity with which the work was conceived, especially the device of lighting from behind and the sensitive chiaroscuro effects, heightens its realism while, at the same time, infusing it with poetry.