Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618 by Diego Velázquez

A robust, well-endowed peasant girl, very ordinary in appearance, is crushing garlic in a mortar. Behind her an old woman with a sober expression on her sharply lined face seems to be offering her culinary advice. The clothing of the women is unpretentious, its tones austere; there is no flashiness, no jewelry, no ornamentation whatsoever. The straightforwardness of the two women, the composure of their bearing and expression, and their sustained attention to their work are indications of their honest natures and their feeling for what is proper. However, the younger woman appears to be preoccupied by something occurring in front of her, which would imply that what we see in the background is, indeed, a mirror, in which is reflected Christ's visit to the house of Martha and Mary.

In the foreground at the right, on the table, are a plate of fish, another plate with two eggs, and a pitcher. Velázquez does not merely concentrate on their simple outward appearance, but probes the essence, the underlying poetry of all of these objects. They are not painted as purely decorative elements, nor are they isolated; each enters into a dynamic relationship with the others and is integrated into the composition as a whole. In this manner, they contribute to the harmony and overall rhythm of the work as well as to its reality and poetic significance.

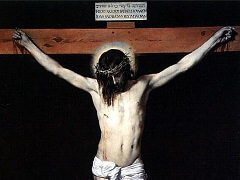

And in the background there is the mirror-image of Christ's visit. In a luminous space, Christ is seated while one of the women kneels at his feet and the other remains standing, behind her.

Unlike Caravaggio and Rubens, Velázquez never excelled as a mystical painter and was even less attracted to that popular religiosity, rooted more in superstition than in genuine religious fervor, to which Murillo was sometimes drawn. Incapable as he was of portraying anything devoid of reality, Velázquez's artistic vision thus interpreted religious themes with a Biblical simplicity infused both with realism and a mysterious poetry.